June 1, 2025

Long-short extension strategies expand the traditional long-only investing playbook. How so? Managers can not only invest more in their highest conviction ideas but also are enabled to bet against stocks they believe will underperform. The result is a portfolio that strives for overall market exposure while aiming for enhanced returns.

What Long-Only Really Means

In a long-only portfolio, a manager buys stocks they expect to rise in value. If they dislike a particular company, the best they can do is avoid it. For small companies, this presents a cap on their ability to profit from negative views on a stock.

Here’s an example. Suppose Company A is 0.10% in the S & P 500 Index. An investment manager that thinks the stock is materially overvalued can simply not own it. If the stock falls to zero, the manager was spot on. How much was that worth in outperformance vis-à-vis the S&P 500? 10 basis points. Hardly a game changer for being so prescient.

Shorting changes that. It allows a manager to borrow and sell a stock today, hoping to buy it back at a lower price. If the stock falls, they profit. This flexibility—going both long and short—helps managers act on their full range of insights, not just the bullish ones.

As Meketa Investment Group, an institutional consultant to large pensions and endowments (including CalSTRS and Arizona State Retirement System) explained:

“The portfolio manager… can effectively achieve a negative weighting that captures her investment beliefs better than merely reducing that stock’s weighting to zero.”

— Meketa Investment Group, 2019

A common implementation of long-short extension is the 130-30 strategy, where a manager shorts 30% of the portfolio and uses the proceeds to buy an additional 30% in their highest-conviction long ideas—resulting in 130% long, 30% short, and a net 100% market exposure.

This additional flexibility becomes especially powerful when paired with factor investing—systematic strategies that tilt portfolios toward so-called anomalies like value, momentum, profitability, and low investment. Historically, these factors have delivered superior risk-adjusted returns across markets over long time periods, as Hsu et al. (2016) outlined, though performance can vary significantly across market cycles.

Why the Short Side Matters

But there’s a catch: much of this outperformance comes not just from owning the winners—but from shorting the losers.

In their peer-reviewed study, The Role of Shorting, Firm Size, and Time on Market Anomalies, Israel and Moskowitz (2013) find:

“Short positions are not only necessary for capturing the full alpha of many anomalies, but they also often provide more statistically and economically significant returns than the long legs.”

Momentum strategies are especially reliant on the short side, where bottom-decile stocks have historically underperformed sharply. Without the ability to short, traditional long-only investors may be effectively leaving half the trade—and half the opportunity—on the table.

This is echoed by Brière and Szafarz (2017), who state:

“Short sales contribute significantly to the mean-variance performance of efficient factor-based portfolios.”

Enhancing Efficiency Through Portfolio Design

This all ties back to a foundational framework laid out by Clarke, de Silva, and Thorley in their 2002 paper, Portfolio Constraints and the Fundamental Law of Active Management. They show that long-only constraints reduce the “transfer coefficient”—a measure of how effectively a manager’s insight (be it factor or traditional stock picking) is translated into portfolio positions. Removing those constraints (i.e., allowing limited shorting) increases this efficiency and the potential for outperformance.

“The loss of efficiency due to the long-only constraint is not trivial. Even the best forecasts lose much of their value if they can’t be implemented through meaningful active positions.”

— Clarke, de Silva, and Thorley, 2002

Real-World Evidence

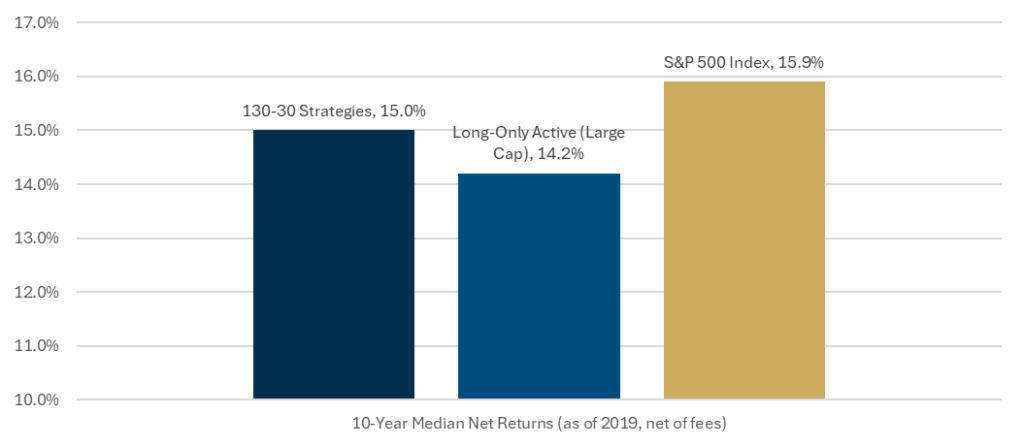

This isn’t just theory. Research by Meketa showed that long-short extension strategies via a 130-30 implementation have produced superior long-term returns compared to traditional active managers, even net of fees.

Yes, both long-short and traditional active strategies underperformed the S&P 500 during the decade analyzed. We offer two observations. First, the period ending in 2019 was a challenging one for most factor-based approaches and fundamental stock pickers, given the dominance of a narrow set of growth stocks. Second, the long-short extension approach effectively halved the shortfall relative to the index, highlighting the potential benefit of enhanced implementation over traditional active management.

Bottom Line

For investors who incorporate factor-based strategies, long-short extensions may offer a more flexible way to express those views. By allowing both long and short positions, these approaches can expand the opportunity set while seeking to maintain market-level risk exposure.

That said, long-short strategies involve additional complexity and cost, and outcomes may vary based on manager skill, implementation, and market conditions. As with any investment approach, they should be evaluated in the context of a broader portfolio and the specific objectives of the investor.

References:

- Meketa Investment Group. “130/30 Long-Short Equity Strategies.” September 2019.

- Israel, R., & Moskowitz, T. (2013). “The Role of Shorting, Firm Size, and Time on Market Anomalies.” Journal of Financial Economics.

- Brière, M., & Szafarz, A. (2017). “Factor Investing: The Rocky Road from Long-Only to Long-Short.” Amundi Working Paper.

- Clarke, R., de Silva, H., & Thorley, S. (2002). “Portfolio Constraints and the Fundamental Law of Active Management.” Financial Analysts Journal.

- Hsu, J., Kalesnik, V., & Viswanathan, V. (2019). Will Your Factor Deliver? An Examination of Factor Robustness and Implementation Costs. Financial Analysts Journal.